Aaron Swartz was a vocal proponent of a free and open Internet and a staunch believer in open access. His Guerilla Open Access Manifesto, written in 2008, is just as powerful and relevant to the world of academic publishing today as it was 6 years ago.

A little over a year ago, the Internet began mourning the loss of this well-loved entrepreneur and pioneer. Tech-savvy academics were shocked by Aaron’s death; some were upset at the handling of his legal case while others called on universities to respond by doubling down on open access to the scientific literature. Meanwhile, the news media were left struggling to explain just what JSTOR was and why Aaron was potentially facing years in prison for downloading a bunch of PDFs.

And then, academics joined together worldwide in a small act of defiant tribute.

It all began when shortly after hearing this news, a few researchers decided to post PDFs of their published articles online under the hashtag #pdftribute. The idea was to honor Aaron Swartz’ dream of free access to knowledge by making one of the articles they had published freely available online.

Within hours the movement had unexpectedly exploded into a worldwide phenomenon, quickly amassing up to 500 tweets per hour and thousands of PDFs shared with the world in equal parts eulogy and protest.

Opening up the PDFs

The Internet-born #pdftribute meme was global in reach, spreading from Twitter through strong networks of research groups and academic institutes. Within a few weeks the hashtag had been used by researchers from a wide variety of academic disciplines spanning all corners of the globe, with every tweet sharing a few words of support and a link to an online copy of that researcher’s published work.

One programmer quickly created a website pdftribute.net to collect links to all of these shared documents. Since academic PDFs are part of what I work with all day, I was curious to take a deeper look inside.

So off I went with 2,400 PDFs in hand, seeking to learn what the documents themselves might have to say about the #pdftribute phenomenon and the researchers who memorialized Aaron Swartz in this unique way. The goal? To understand who took part in #pdftribute and what they shared, purely through the lens of their PDFs.

Beating Babel

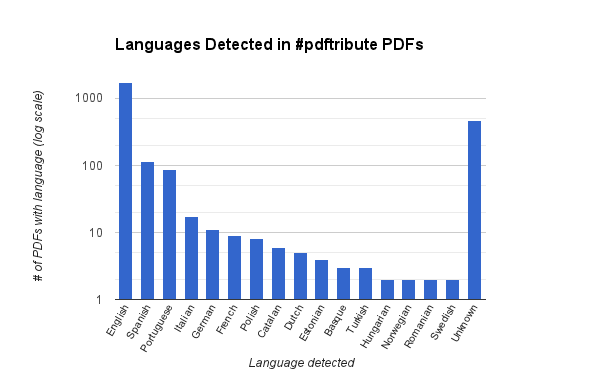

Although some scientists may take for granted the English-centric nature of their field, research is a global and multilingual pursuit. A sizable fraction of journal articles are published in non-English languages (though the prevalence of non-English journals is decreasing) and it was immediately apparent that many #pdftribute PDFs were written in different languages.

The vast majority of #pdftributes were English articles as expected, but I was surprised that Spanish and Portuguese were the next two most common languages—and by such a wide margin over other Romance languages. If the meme had caught on in Europe, surely we would have seen more German, Italian, and French activity too.

So what exactly made Spanish-speaking researchers want to join in #pdftribute by sharing articles published in their native tongue? The answer may lie in Swartz’s travels to Brazil: he made an especially strong impression on Ronaldo Lemos, the leader of Creative Commons Brazil, whom he met in Rio de Janeiro in 2009. The prevalence of Spanish and Portuguese articles suggests that Aaron similarly inspired, directly or indirectly, many other South American researchers during his life.

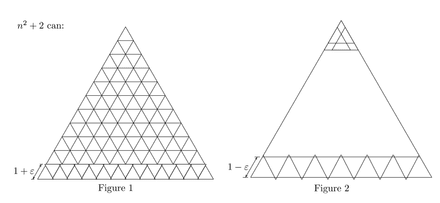

Pictures with a Thousand Words

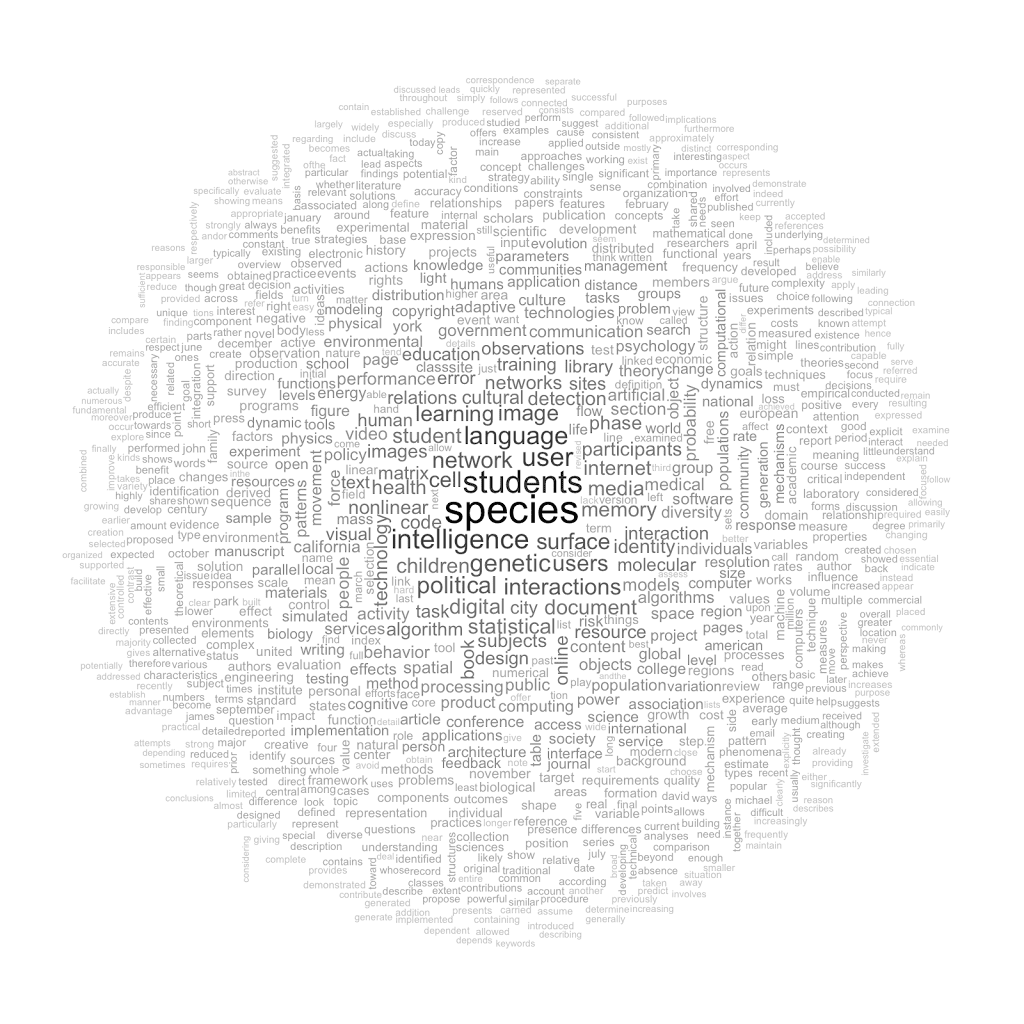

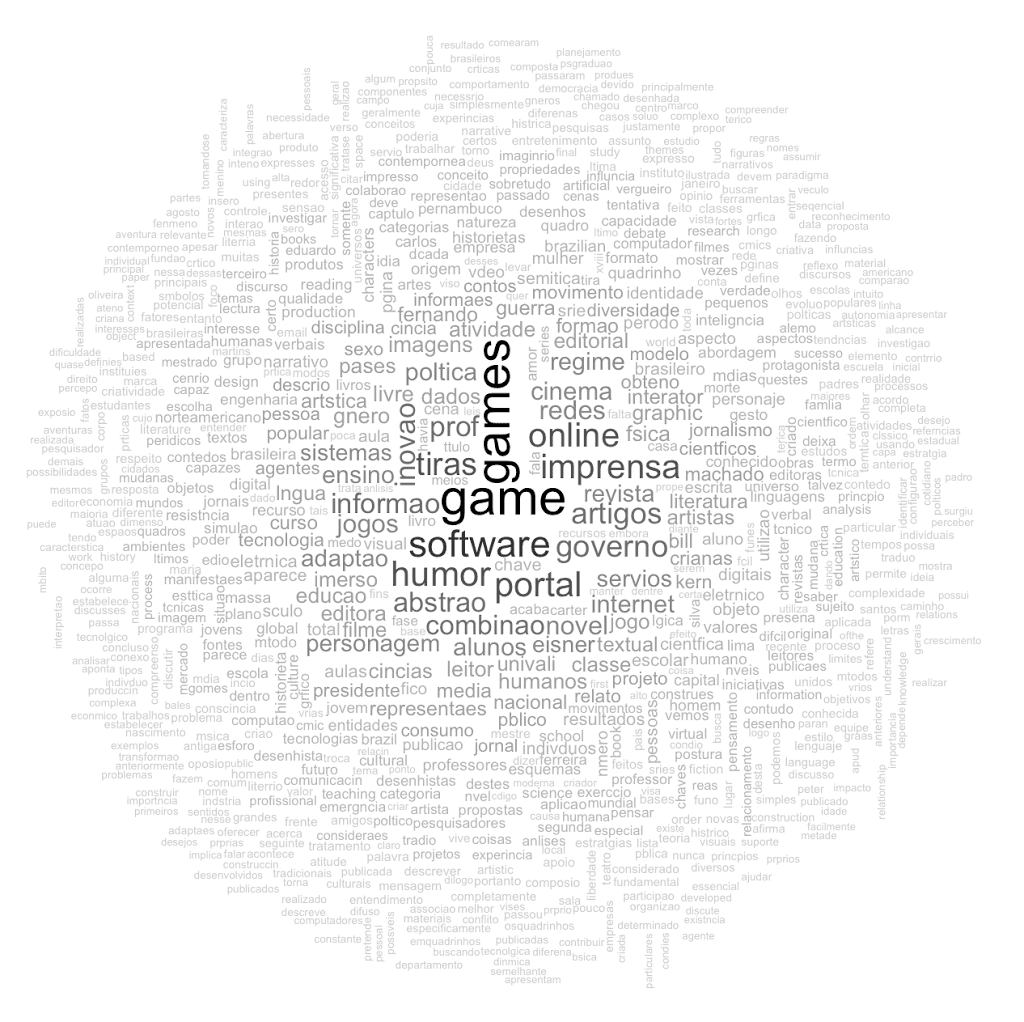

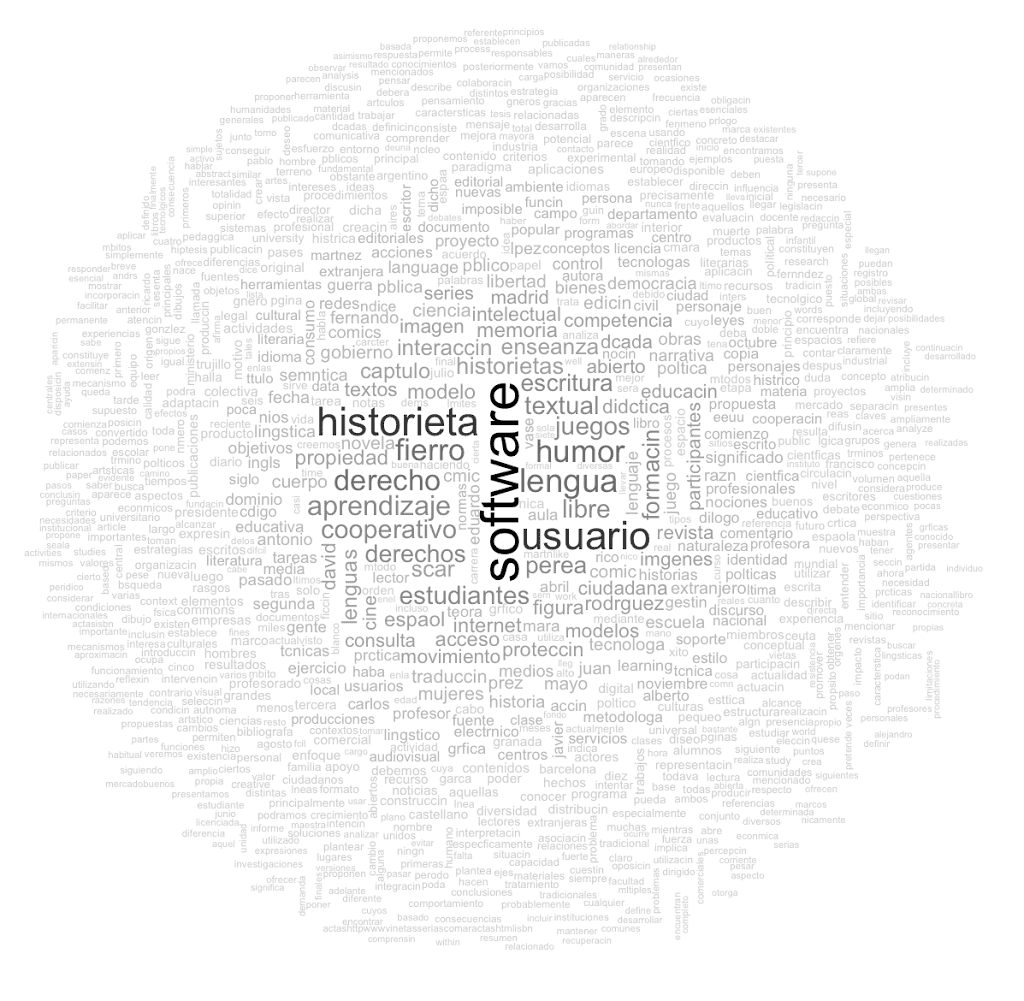

To get a sense for what kind of topics were being discussed in the shared papers (and what type of researchers were most active in #pdftribute), I created word clouds from the text of all English, Spanish, and Portuguese documents.

A number of biology-related words like species, genetic, cell, and molecular pop out in the English-language word cloud, as well as physics (nonlinear, phase, force, energy) and computer science (video, matrix, memory) related concepts. You can also find a handful of words related to government and politics—which Aaron spent many of his post-Reddit years trying to reform—such as political, government, policy, and movement.

The Spanish and Portuguese texts showed a smaller overall number of dominant words, likely due to the smaller number of documents to analyze. But strangely enough, English words like software and games were strongly enriched in these articles, suggesting that researchers in software and videogames were heavily involved in the non-English component of the #pdftribute campaign.

Digging into the Metadata

Next I imported all #pdftribute PDFs into Paperpile to extract more complete citation metadata. Paperpile parses an article’s title and authors from the PDF and matches this data with PubMed and Google Scholar where possible. This is an easy way to collect accurate citations from an otherwise unorganized mess of PDFs.

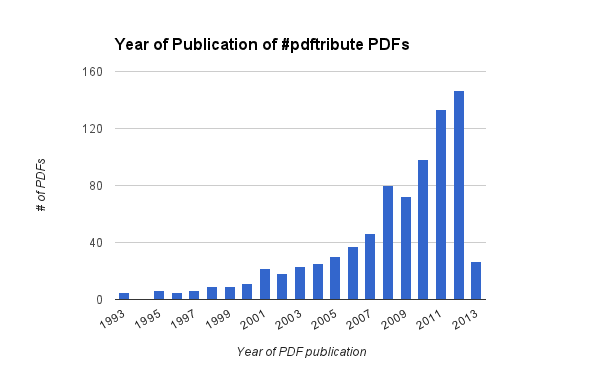

Just over 2,200 PDFs were imported successfully, and Paperpile was able to collect good citation data for 805 of those articles. Looking at the publication year, it’s clear that most researchers chose to share their most recently-published articles, with relatively few PDFs from more than 5 years prior. And the most common types of publications shared were journal articles, followed by conference papers and book chapters.

| Type | Count |

|---|---|

Journal Article | 1432 |

Miscellaneous / Unknown | 683 |

Conference Paper | 94 |

Book Chapter | 43 |

Preprint Article | 5 |

Book | 1 |

I was able to further break down the data by grouping articles by the title of the journal in which they were published. Looking at the most common journal names, the prevalence of biology-related terms in the English-language word clouds becomes clear: many of the articles were published in well-known biology journals like Biological Conservation, PLOS Genetics and Nature Genetics.

| Journal | Count |

|---|---|

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA | 17 |

PLOS One | 14 |

Nature | 11 |

Tellus A | 9 |

Science | 9 |

Icarus | 9 |

New Directions for Student Services | 8 |

New Media & Society | 7 |

J. Exp. Anal. Behav. | 7 |

Biological Conservation | 7 |

PLOS Genetics | 6 |

Nature Genetics | 6 |

Traffic | 4 |

Surface and Interface Analysis | 4 |

Phys. Rev. E | 4 |

One might say that #pdftribute contributors liked to show off a bit by sharing their best work, as articles from the top-tier journals Nature and Science—two of the so-called “luxury journals” according to Nobel laureate Randy Sheckman—were among the most common. Sheckman famously railed against these journals on the eve of his Nobel speech last year, so he might be happy to see that PNAS, a journal he used to edit, took the #1 spot as the most frequently shared.

The story of the #4 journal Tellus A is also worth relating, as it represents a step towards the kind of grassroots movement towards open access that Aaron had long been hoping for.

Tellus A, a small meteorological journal founded in 1949, had 9 papers shared in #pdftribute—a surprisingly large number given its relatively small publishing output. A clue to this over-representation may lie in the journal’s move in 2012 from a closed-access subscription model to a fully open access publisher. In one fell swoop, the journal’s entire editor and author community embraced open access with great success. This bold shift to open access gave Tellus A authors another reason to be proud of their journal, and may have motivated their resulting enthusiasm for #pdftribute.

A Lasting Digital Legacy

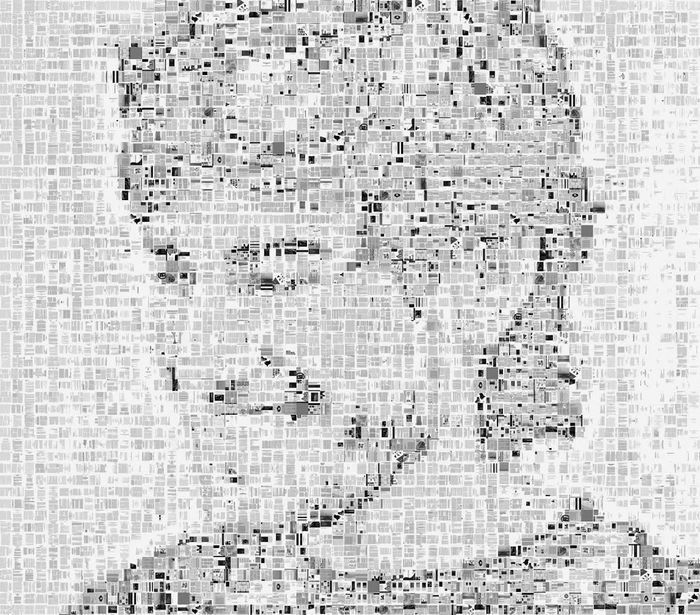

As more research societies and organizations move to open access—like the monumental move in particle physics to transition dozens of journals from subscription to OA models—I am optimistic that Aaron’s powerful words and staunch belief in open access will be his most lasting legacy for scientists. His actions in pursuit of that ideal, misguided though they were, could have been more easily forgiven and forgotten. But as the PDF files themselves revealed, researchers from around the world have vowed not to forget Aaron Swartz, lending their voices to the Internet memorial that began a year ago with the unassuming name #pdftribute.

Appendix: Technical Details

For those who may be interested, below are some technical detail on how the PDF analysis was performed.

First, all #pdftribute PDFs were downloaded from pdftribute.net in early 2013. Roughly 2,400 PDFs were collected, totalling 2.75Gb of space. Text from each PDF was extracted using the pdf_extract package from the npm repository.

To separate articles by language, I used the cldr package in R, which is based on the same C++ language detection engine used in Google’s Chrome browser. When run on a given text file, cldr returns the most likely language along with a confidence value. A confidence cutoff of 70% was used here to separate PDFs into separate languages.

To get a sense for what kind of topics are covered in the shared papers, I used functions from the tm package in R to extract and analyze the text from each set of PDFs. Roughly following the tutorial from One R Tip a Day, the wordcloud R package was used to plot word clouds separately for the English, Spanish, and Portuguese documents.

I then imported the set of PDF documents into Paperpile, which analyzed the text to match each paper with accurate citation metadata from PubMed, Google Scholar, or CrossRef. After exporting the Paperpile references in Bibtex format, I analyzed their contents using regular expressions and a simple shell script.

Finally, the image on display at the top of this post was created by first creating thumbnails of the first page of each PDF using ImageMagick, then using AndreaMosaic to arrange the PDF thumbnails in a photomosaic of Aaron Swartz. A CC0 licensed version of this mosaic is available at http://imgur.com/vqwZ7u1.