Science is a peculiar business in the modern world. It is one of the very last strongholds of a kind of “ethical code” that implies that published data is true — or at least solid within the realm of technical or biological limitations. Scientists don’t cheat. Not even on themselves. Science, the world, and the universe (as scientists like to believe) rely on scientists to be honest. That is the reason why fraud in science still causes such an earthquake, rocking the foundations of the field. The mere accusation of fraud can end a scientific career, dishonoring prior achievements, and, in the worst case, end in disaster.

The Austrian biologist Paul Kammerer, and his “case of the Midwife Toad”, is still one of the biggest unsolved mysteries of scientific fraud, in which a tragic suicide may have been a confession of guilt. It could have been, however, a final acknowledgement that his work of a lifetime will never be viewed without suspicion ever again after such calumny.

Gentleman, lover, and aquarian

He named his first-born daughter Lacerta (Latin for lizard)

The stage for what will turn out as possibly the biggest scientific scandal of the 20th century is set in turn-of-the-century Vienna, where a young Paul Kammerer starts to work at the Vivarium, an experimental animal lab. His tasks involve breeding reptiles and amphibians, and he brought with him such an astonishing aptitude for providing creature comfort, that he soon started experimenting with even the hardest to breed animals. In his spare time he played the piano, composed symphonies, and moved in the circles of the Viennese high society. Being somewhat of a sonnyboy with dashing looks, he had several affairs with famous women of his time, including Alma Mahler, who later became his lab assistant for a while.

However, it was his love of animals that fostered his reputation as one of the shooting star scientists of the time. Kammerer joined the current grand debate on evolution - and set out to prove that acquired traits can be inherited, following the theories of Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck.

Following Lamarck’s ideas, Kammerer set out to prove that acquired traits can be inherited

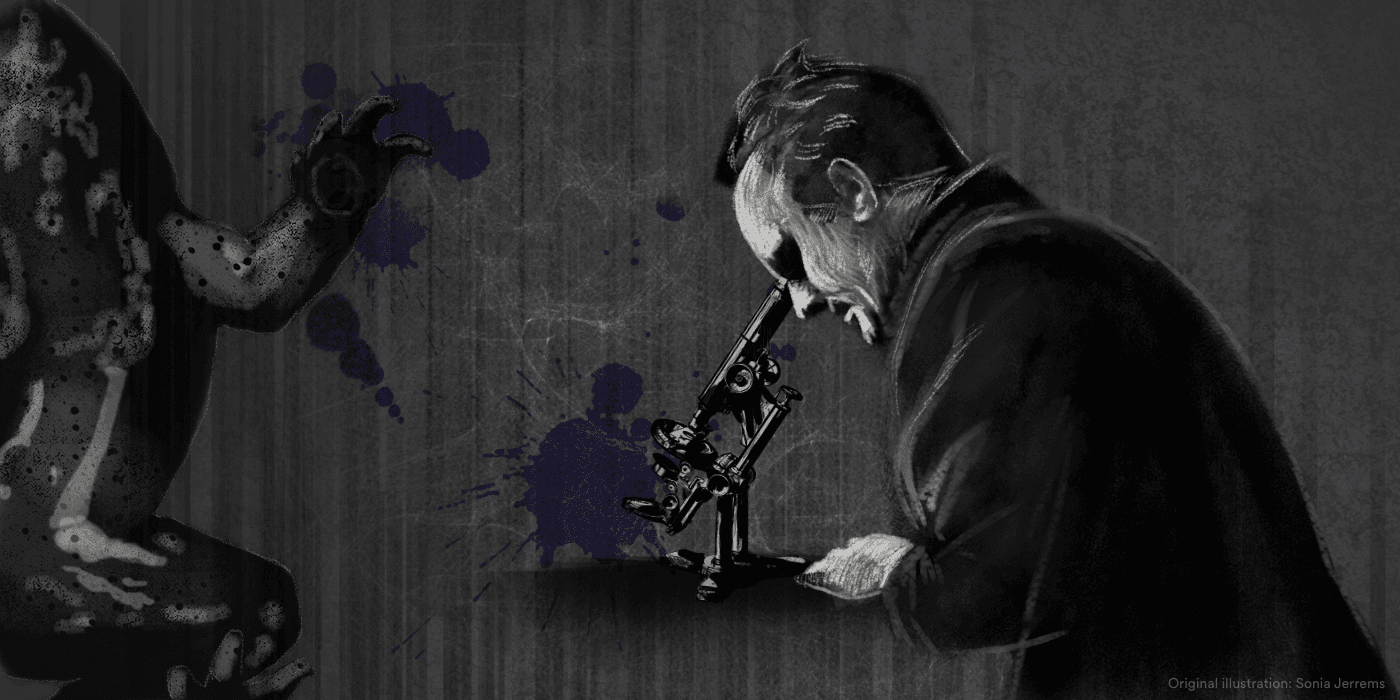

In his experiments, he demonstrated that fire salamanders and alpine salamanders adapt to their specific environments, even if these environments are not their natural habitats, and that these adaptations are passed on to the next generation. Likewise, he showed that the blind eel-like salamander proteus would develop eyes if brought up not in daylight, but in red light. Again, these developments were confirmed in the next generation. In total, Kammerer published 130 articles in the time from 1902 to 1908, working at the Vivarium.

A unique workplace

The Biologische Versuchsanstalt (Biological laboratory) was founded by three young Jewish scientists in 1903 with the goal to promote experimental and quantitative biology. Located in an old Aquarium (“Vivarium”) built for Vienna’s World Exposition in 1873, it became quickly a leading international and interdisciplinary research institution.

It was open for guest scientists from all over the world and also offered opportunities for women who could not work at the University of Vienna at the time.

The unique institution was closed immediately in 1938 after the Anschluss of Austria to national socialist Germany. All Jewish scientists (15 of 22) lost their position, 7 of which died in the Holocaust.

The slippery business of the midwife toad

However, his most famous proof of concept experiment was that of the midwife toad. In contrast to their close relatives, midwife toads indulge in a surprisingly terrestrial lifestyle for amphibians - they copulate and fertilize their eggs on land, not in the water. In line with this habit, the male midwife toads do not have nuptial pads. Their close relatives, such as the fire-bellied toads, with a more aquatic lifestyle, need these nuptial pads to hold on to slippery females during copulation in water.

His experiments were so convincing, that Kammerer became a celebrity

In his breakthrough long-term experiment, Kammerer showed that after forcing midwife toads to mate in water (by increasing the air temperature), they would develop rudimentary nuptial pads. These were passed on to and became more prominent through the generations, eventually forming proper nuptial pads. Based on the understanding of genetics at the time, Kammerer thought that this experiment clearly showed that genetic traits can be acquired in adaptation to the environment, and that these then enter the gene pool to be passed on to the next generation.

His experiments were so convincing, that Kammerer became a celebrity, touring the world with his results, and was recognized as one of the most important scientists.

How to kiss a toad

He wanted his experiments to work so much, that he may have unintentionally overestimated results

Standing in the spotlight does not come without shadow obviously, and Kammerer’s work triggered a fair share of criticism. One of the biggest problems with his work was that many of his experiments were not reproducible, despite his efforts to describe the experimental design in great detail. However, this may be attributed to the fact the Kammerer was simply an outstanding expert on breeding these species. He seemed to have had an incredible gift in breeding and training amphibians and reptiles, that most reviewers would find inexplicable and certainly hard to follow. Alma Mahler, his lover and lab assistant at the time, described his affection towards his animals, saying he would actually kiss his toads. Above that, she also stated that he wanted his experiments to work so much, that he may have — unintentionally — overestimated results.

Every scientist is probably aware of the danger of the loss of bias, especially as an expert in a field - how many other people in the world would have been able to distinguish a callus on a toad’s toe from an emerging nuptial pad, other than Kammerer? However, while it is a fine line between over-enthusiasm and fraud, it is a definite line.

The fall

The controversial nuptial pads were discovered to be ink stains. Kammerer shot himself six weeks after the accusations became public

After Kammerer’s success provided him with a call to the Soviet Academy of Science in Moscow, his biggest antagonist, the American zoologist Gladwyn Kingsley Noble went to Vienna to inspect the last remaining preparation of Kammerer’s midwife toads. In response, he published an article in the scientific journal Nature in August 1926, describing his findings: the alleged nuptial pads were discovered to be injected ink stains. This article set an end to the career of Paul Kammerer, stigmatising him as fraudster and deceiver. A month later, Kammerer sent a letter to his institute in Moscow, stating that he finds himself unable to live with “the thwarting of his life’s work”. He shot himself only a month later on a hill overlooking an idyllic village near Vienna.

In his suicide note, he dedicates his body to be dissected at the medical university, hoping his colleagues may find “traces in my brain of what they were unable to find in the living expressions of my intellectual activities”. Before his death, he confirmed the findings of Noble, but, until the end, he asseverated his innocence in these fraudulent deceptions.

Guilty or not?

After Kammerer’s suicide was linked to Noble’s article in Nature, the public was quick to condemn his action as proof of guilt. Many, however, stood with Kammerer, convinced that he was framed. Seven decades after Kammerer’s death, the jury is still out on what really happened in the “case of the Midwife Toad”.

Was there a conspiracy? Disapproval of eugenics and Lamarckian views did not comply with current views of the scientific establishment

While even Kammerer himself agreed that the preparations investigated by Noble had ink injected, it is not clear how this simple trick would have evaded the many scientists before who observed Kammerer’s specimens or preparations, as he had always been eager to show these to visitors, provided they arrived at mating season. In addition, other parts of the experiments went unnoticed in the condemning paper — such as the preference of the aquatic lifestyle, that was also acquired and inherited, or the changed architecture of the jellycoat surrounding the eggs. Noble would have been unable to observe these details described in Kammerer’s publications, as his toad strains also fell victim to war torn Europe.

Could it have been a jealous lab assistant who framed him? Or was there a bigger conspiracy? Kammerer was half Jewish and throughout his lifetime victim of the growing antisemitism. His disapproval of eugenics in conjunction with his Lamarckian views did not comply with current views of the establishment. These were probable reasons for the continuous denial of a professorship at the university of Vienna, which belied his position as one of the leading scientists of his time.

While his case inspired the creation of plays, books and films — the only real resolution of it lies in the hands of scientists.

A socialist hero

In the Soviet Union of the 1920s, scientific facts were not only the results of what scientists found in their experiments but also what the communist party declared to be scientific facts. The party favored the idea of inheritance of acquired traits — also drastically documented by Trofim Lysenko’s “pseudogenetics” that held the biological field in the Soviet Union hostage for decades.

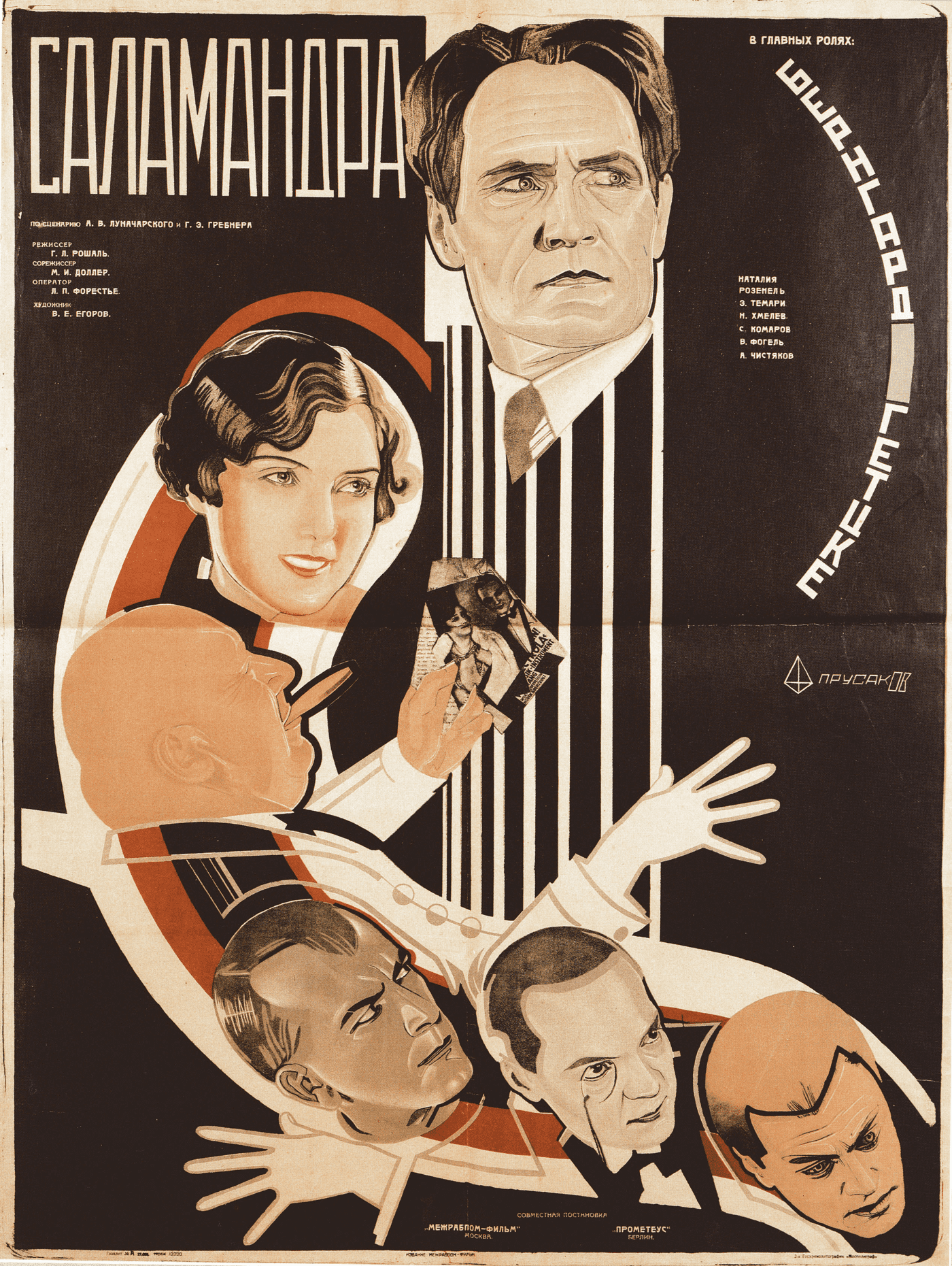

Paul Kammerer’s Lamarckian ideas were readily accepted in the Soviet Union. In 1928, Kammerer’s life became the story for the movie Саламандра (“Salamander”). In a propagandistic distortion of his life, Kammerer is portrayed as a socialist hero hunted by regressive scientists and Catholic clergy.

The most notorious cold case of science fraud is not closed

So far, Kammerer’s experiments have not been repeated, mainly due to the fact that midwife toads seem to be inherently difficult to be pushed to mate in water under modern laboratory conditions, without the special relationship Kammerer seems to have had with his animals.

Modern epigenetics could offer a model for Kammerer’s observations

However, a recent publication argues that reproduction of the experiments could lead to a dramatic shift in the position of Kammerer in the history of science (Vargas, 2009). The paper by Alexander Vargas argues that Kammerer may have been the discoverer of epigenetics, and offers a model for his observations, including potential parent-of-origin effects and Mendelian inheritance in subsequent generations that Kammerer describes in his publications. The development of the nuptial pads could be based on sensitization of the eggs to methylation in water, in combination with a change in the imprinting.

Is this the missing piece in the story? Whatever we’ve learnt so far about this case, one thing seems certain. Nothing is simple and uncontroversial. Vargas’ paper offering epigenetic explanations was immediately rebutted by another paper (Gliboff, 2009). In the abstract it reads “Vargas is seriously misinformed about what Kammerer did”. So even more than 80 years after Kammerer’s death his midwife toads cause controversy.

Another important finding in support of the conspiracy against Kammerer is the rare presence of nuptial pads on midwife toads in the wild, confirming the plasticity of their genome that has the potential to still develop these traits of their aquatic relatives.

Whether Kammerer’s reputability will ever be vindicated, or whether history will continue to remember him as one of the biggest frauds in science remains to be seen. But Paul Kammerer certainly still holds the position as one of the best and most empathetic aquarians of all times.

About this series

This series is about the tragic lives and deaths of three Austrian scientists who shook the foundations of physics, mathematics and biology.

They opened their mind to a world beyond the boundaries of what was accepted at their time. Their controversial and dangerous ideas led them to the question: is this world still worth living if you’re alone in your grasp of something ungraspable?