One thing that the Internet couldn’t live without is links. In fact, the Web is pretty much defined as a collection of links between virtual resources, and a fundamental part of good web citizenship is providing links to related pieces of content. Helpful, working links are vital to the health of the web.

So it goes with papers. In today’s complex ecosystem of academic publishing, a single research project may yield several distinct web-based outputs: a preprint manuscript here, peer-reviewed paper here, and dataset over there. The ease with which an author can now disseminate her different research outputs is incredible. With sites like Arxiv, Figshare, Dryad and the nascent Peerage of Science, your data, figures, and manuscripts can live in many different places on the road toward publication.

However, a healthy Web doesn’t necessarily mean a healthy Web for scientists. If websites and search engines aren’t providing the links you need to effectively mine the literature, you’re stuck. Which is why for this post, we stepped into the world-wide web for research and asked whether our papers are getting the links that we, as authors and readers, deserve.

Links or it Didn’t Happen

The existence of separate journals, preprint servers and data archives is itself a good thing — let the data specialists handle data, let the publishers handle publishing, et cetera. But problems arise when each output lacks the context of its associated information. Without this context, your readers will be stuck: a dataset isn’t much good without its corresponding paper, and a preprint might be out of date compared to its published version. Thus, cross-links between these related pages are important to gaining a complete understanding of a given research project.

Lucky for us, plenty of smart people are working hard to make sure these cross-links are easily available. It’s a near-miracle that organizations like CrossRef (which manages the ubiquitous DOI registry for academic publishers) exist, and NCBI has supported rich cross-linking in PubMed through its LinkOut service for over a decade. More recently, the DataCite consortium enabled smaller organizations like figshare and Dryad to create permanent DOIs for user-uploaded figures and datasets. A trustworthy permanent identifier can go a long way toward making cross-links a reality.

The final step in the chain is actually displaying the links to users. Unfortunately, this is where glossy-eyed optimism about linked data is often met with disappointment. Each publisher, search engine, and data provider needs to make a decision on how and when to provide cross-links. Some do this better than others, but the overall experience for researchers can be haphazard and inconsistent.

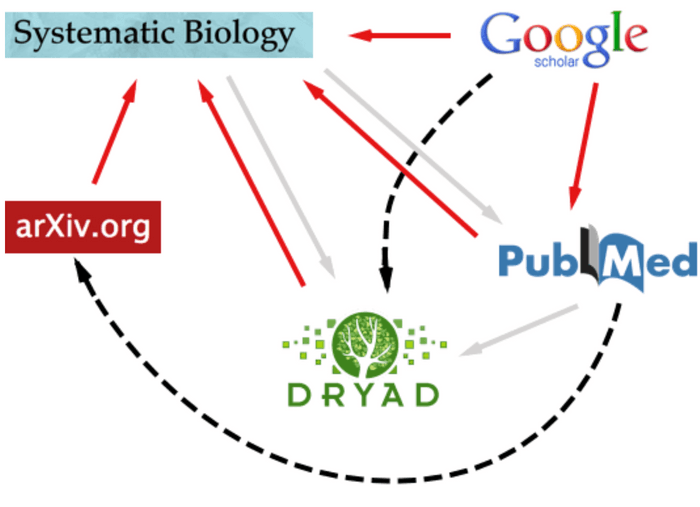

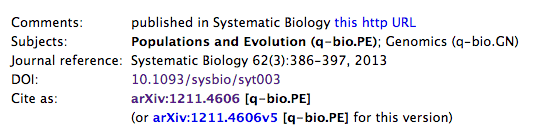

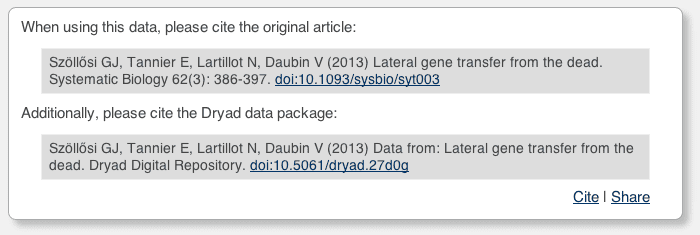

Let’s take a look at a recent example. In late 2012 four systematists (Gergely J. Szöllősi et al.) completed a study on lateral gene transfer in phylogenetic methods. The authors posted their manuscript to arXiv (http://arxiv.org/abs/1211.4606), deposited a dataset in Dryad (http://datadryad.org/resource/doi:10.5061/dryad.27d0g), and ultimately published the article in Systematic Biology (http://sysbio.oxfordjournals.org/content/62/3/386). Making full use of the repositories available to them, this study now lives in three distinct, but related, places online. The reasons to want cross-linking between these pages are obvious: a reader of the full-text article may want to look at the Dryad data to verify its consistency; someone who lands at the arXiv preprint may wish to see its final published form; and if the article weren’t open access (which in this case it is), a visitor to the Systematic Biology site may like to know that a preprint version is freely available on arXiv.

I wanted to find out how each of these sites stacks up in terms of cross-linking, looking specifically at (a) the existence of cross-links between resources, and (b) the discoverability of these links within the page. So I visited each site and checked how it presents cross-resource links to the user.

arXiv and Dryad: Simple but Effective

As expected, both arXiv and Dryad simply point to the DOI of the final published paper, and both sites feature the link prominently. The arXiv page includes a whopping three mentions of the associated published paper, with a textual citation and two direct links. Dryad displays a compact infobox, containing a complete citation and link for both the published article and the Dryad dataset. The only possible improvement here would have been a direct link between the arXiv preprint and the Dryad repository; perhaps arXiv should think about adding a “Data reference” field in the future, especially as researchers become more aware of the need for long-term archival of their data outputs.

Systematic Biology: Buried in the Depths

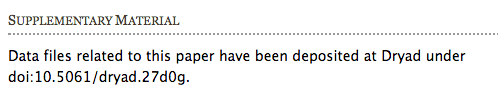

When a reader views the abstract page of the Szöllösi et al. article in Systematic Biology (an Oxford University Press journal) there’s no indication that either the arXiv preprint or the Dryad dataset exist. The lack of a Dryad reference is surprising, especially since Systematic Biology is listed as an “integrated journal” on Dryad’s website. So where is the link to the Dryad data?

It turns out you need to view the full-text version of the article to find any reference to the Dryad dataset. And even then, the link isn’t a link — it’s a plain-text DOI that readers need to copy-paste into Google to figure out how to actually view the Dryad dataset. This integration technically fulfills the cross-linking requirements, but leaves much to be desired in terms of discoverability.

The lackluster links from Systematic Biology highlight an important problem facing most researchers scouring the web for articles: there are hundreds of different academic publishers, and each one has its own web design and linking capabilities. While some publishers are fully embracing the idea of cross-links — Elsevier’s Science Direct is actually a forerunner in this area (see their recent article on data linking; a screenshot of their Dryad links is below) — others are lagging behind. When interfaces are inconsistent and the availability of information is haphazard or unpredictable, readers suffer.

Search engines: Missed Opportunities

Search engines and abstract databases are major drivers of traffic to journal articles and preprints, and they offer something that publishers cannot: a standard and consistent interface when browsing articles from different journals and fields. Users love Google Scholar for its speed and simple interface, while some biomedical researchers never set foot beyond PubMed. These services already drive a large proportion of traffic to publishers’ websites, so they could benefit readers by cross-linking to related data and preprints directly from their results pages. How do they fare in this regard?

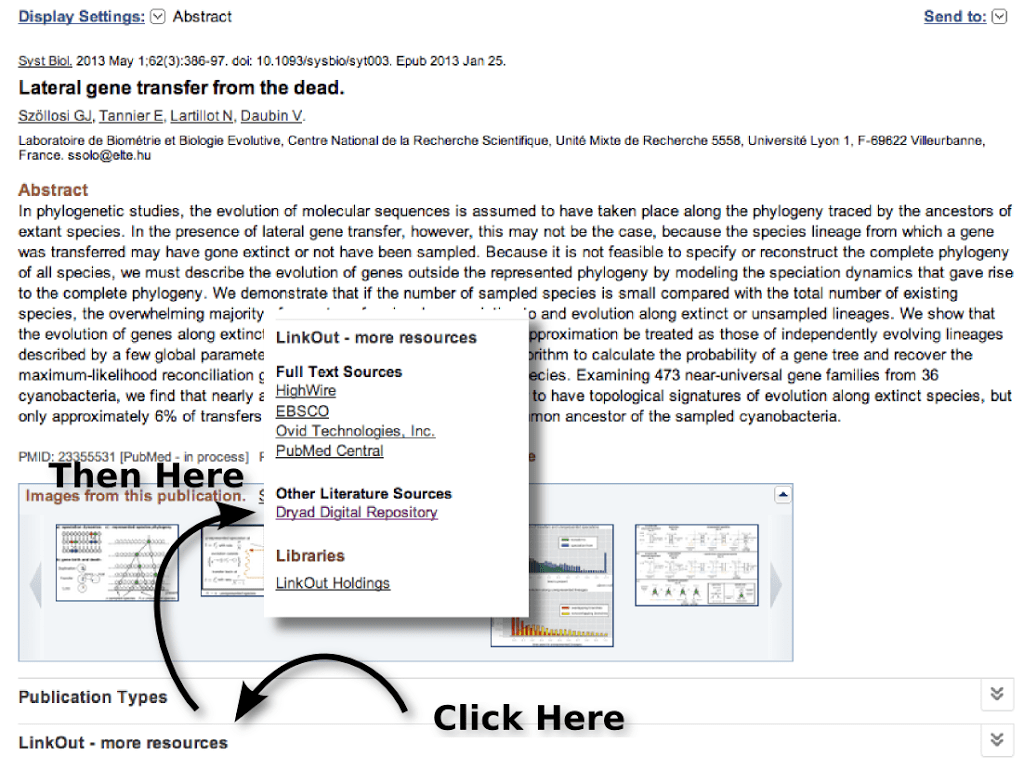

The short answer is: not so well. Google Scholar links to Systematic Biology and PubMed, but misses the arXiv preprint and the Dryad dataset. PubMed does technically include a link to the Dryad data, but it’s buried deep — to even see if there’s a linked dataset available, you need to first click the LinkOut button, then find Dryad within the cluster of links that appears. Not exactly the world’s best link placement!

And if this article weren’t open access, surely a PubMed visitor would want to know that there is a freely available arXiv preprint, allowing them to read the authors’ initial write-up and decide whether or not their research is relevant.

So it seems there’s a bit of a missed opportunity for widely-used literature search engines to feature cross-links between datasets, preprints and articles. Given that PubMed invested so much in its LinkOut service (and that Dryad diligently provides these cross-references to PubMed) it’s a shame that such a useful link is nearly impossible to find.

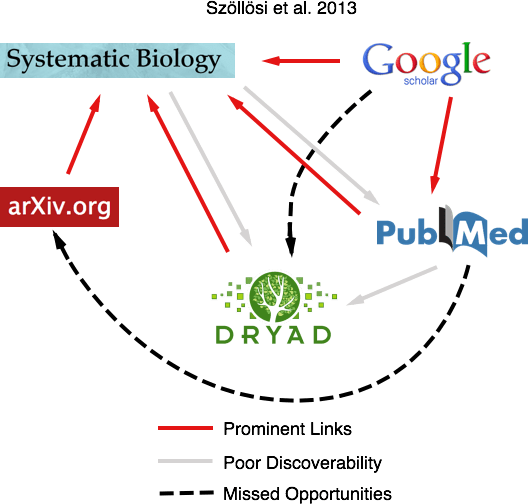

Always jumping at the chance to make a figure, I drew up a quick schematic summarizing the availability of links between five important web destinations for the Szöllösi et al. article. It becomes clear that, while links pointing toward the publisher’s page are ubiquitous, there are some annoyances: veiled or missing links from the publisher’s page, and some glaring omissions and missed opportunities.

However, I’m hopeful that the main holdups here are merely technical and that we’ll be seeing more of this valuable cross-linking in the future. With services like arXiv and PubMed’s LinkOut, much of the groundwork for rich cross-linking has been laid. Now it’s up to the publishers and search engines to make effective use of these associations.

Once these links become the norm, even ostensible competitors in the academic space may find themselves becoming fast friends. Links are a useful service to users — not just because they improve search engine discoverability for everyone, but also because when the reader benefits, each individual stakeholder shares in the reward.

Our Solution: Diverse Links, Simple Interface

I’ll wrap up this post by showing how we approach cross-linking between research outputs in Paperpile, our web-based reference manager. Although it’s a small detail, links are at the heart of any web-based app and so we pay special attention to get links right in our own small part of the web.

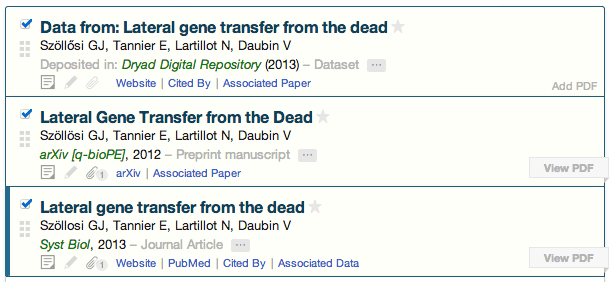

Since you might want to separately cite the dataset, preprint, and journal article, Paperpile imports them as independent entities in your library (see the gray text distinguishing each item type). But we collect as many cross-links as possible when importing items from the web. So, the Dryad dataset includes an “Associated Paper” link; the arXiv preprint has an “Associated Paper” link; and the actual paper has a link to “Associated Data”. The existence of linked data is immediately apparent, and a single click takes you straight to the corresponding Dryad webpage.

We checked in with the team behind Dryad to see what they thought about this solution. Hilmar Lapp from the project posted that these cross-links “hit it out of the box.”

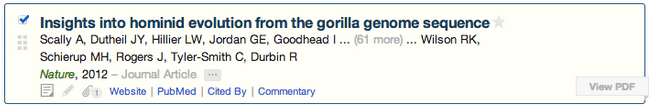

This approach also works for papers that are published with an associated commentary article. PubMed tracks whether a paper is primarily commenting on another PubMed article, and we use that data to include “Commentary” link which takes you to the relevant comment piece.

Most of the time you won’t see these special links within Paperpile, partly because many authors are only just discovering and beginning to use these modular services. But when it’s there and you click on it, a link can make the difference between gaining new knowledge and being left in the dark.

Going forward

Given how web-based life seems to be these days — admit it, you’ve got at least a dozen tabs open alongside this blog post — we think the existence of easily accessible links between related web resources is more important than ever. Links are not just about search engine rankings or driving pageviews; rather, they’re about making the lives of researchers and readers easier by providing a more complete context within an increasingly modularized body of literature.

So we’re happy to see a number of players in the world of academic publishing and archiving forming fruitful web-based collaborations: the integration of Science Direct with Dryad is a notable achievement, and PLOS has been very active in this area, announcing integrations with both figshare (link) and Dryad (link) in recent months. Nature Publishing Group has also followed suit, announcing recently that its upcoming Scientific Data journal will have built-in Dryad and figshare integration.

These high-level developments are positive, to be sure. But what can you do, as an author or reader, to help push the web of research forward? The best action is to advocate for effective cross-links in your own future publications. If you posted your manuscript or a dataset to a service like arXiv, Dryad, PeerJ Preprints, figshare or F1000Posters and are now publishing your article in a peer-reviewed journal, contact your publisher about including a citation or link to your original preprint or dataset. While many publishers already allow preprint archiving, we saw in the Oxford University Press example that an explicit citation or link is rarely included in the published version of record. Pressure from authors and readers may motivate publishers to create effective cross-links, which would benefit everybody in turn.

With the combined efforts of proactive publishers, engaged readers and web-savvy service providers, we are optimistic that the future of linked data is bright. Despite the often heated rhetoric surrounding issues like open access and peer review in scientific publishing, every stakeholder in this ecosystem is dedicated to improving the flow of knowledge and making researchers’ lives easier. Cross-links are like handshakes on the web, and we embrace the idea that a bit more hand-shaking might help us find unexpected friends.