If you think that people who deliberately engage in dubious scientific practices like plagiarism, falsification of results, or attendance at fake conferences represent the worst of scientific misconduct—then you have clearly never heard of Elena Ceausescu.

The author of numerous scientific publications and the recipient of multiple honorary fellowships and degrees, Elena Ceausescu was one of the most respected scientists of her time. Yet, she wasn't even a scientist. She was not even very bright—in fact, almost illiterate—but, through devious and fraudulent means, she managed to become one of the most lauded chemists in the mid-twentieth century.

The dictator's wife

Elena Ceausescu (1916-89) was the wife of Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceausescu (1918-89). During the 1970s and 80s, she was one of the two most powerful women on earth (the other was was Margaret Thatcher, the Prime Minister of Great Britain).

Her reputation was falsely built up thanks to a fraudulent PhD, appointments to Central Committee positions, and extensive propaganda.

Over the course of Ceausescu's rule, Nicolae and Elena constructed a personality cult around themselves, which in many ways paralleled those of Mao, Stalin, and Hitler. This cult positioned Elena as the doyen of the European scientific community and as an academic powerhouse whose publications and international recognition were the result of sustained hard work.

Yet, in reality, Elena's success was a fiction. Her reputation was falsely built up thanks to a fraudulent PhD, appointments to Central Committee positions, and extensive propaganda—all helped along by the intervention of the Securitate, Romania's brutal secret police.

The path to prestige

Elena Ceaucescu was born into a peasant family in a small town near Bucharest. After dropping out of school at 14, she moved in with her brother in the capital and held a variety of jobs, many of which she lost because she lacked skills and education. After her death, a former schoolteacher—who had kept one of Elena's report cards for decades—attested that she had failed nearly all of the subjects that were then taught in Romanian schools (Behr 67).

Her interest in chemistry arose when she was briefly employed in a laboratory. In her free time, she attended meetings of the Youth Communists' League, where she met her soon-to-be husband Nicolae.

She failed nearly every subject that was taught in Romanian schools.

As Nicholae began his rise to power in 1965, Elena found herself sidelined, despite her previous work as a communist activist. Nicolae refused to share power with her and Elena's gender and lack of education barred her from true political ascendancy within the Party.

Driven by a desire to be powerful and respected, and buoyed up by Stalinist ideas about gaining prestige through scientific acumen, Elena turned to the field of chemistry. She believed that a respectable scientific career, enhanced by prodigious publication and academic titles, would provide her with the very power and prestige that she ostensibly lacked.

An indefensible career

Elena began attending night-school courses in chemistry at the Bucharest Municipal Adult Education Institute. She was soon expelled because she cheated on an exam and never received a bachelor's degree. In fact, the teacher who oversaw the infamous exam "lived in fear of his life for decades afterward" (Behr 140).

Elena's PhD in chemistry was based on a thesis defense that never occurred. Indeed, there was nothing to present.

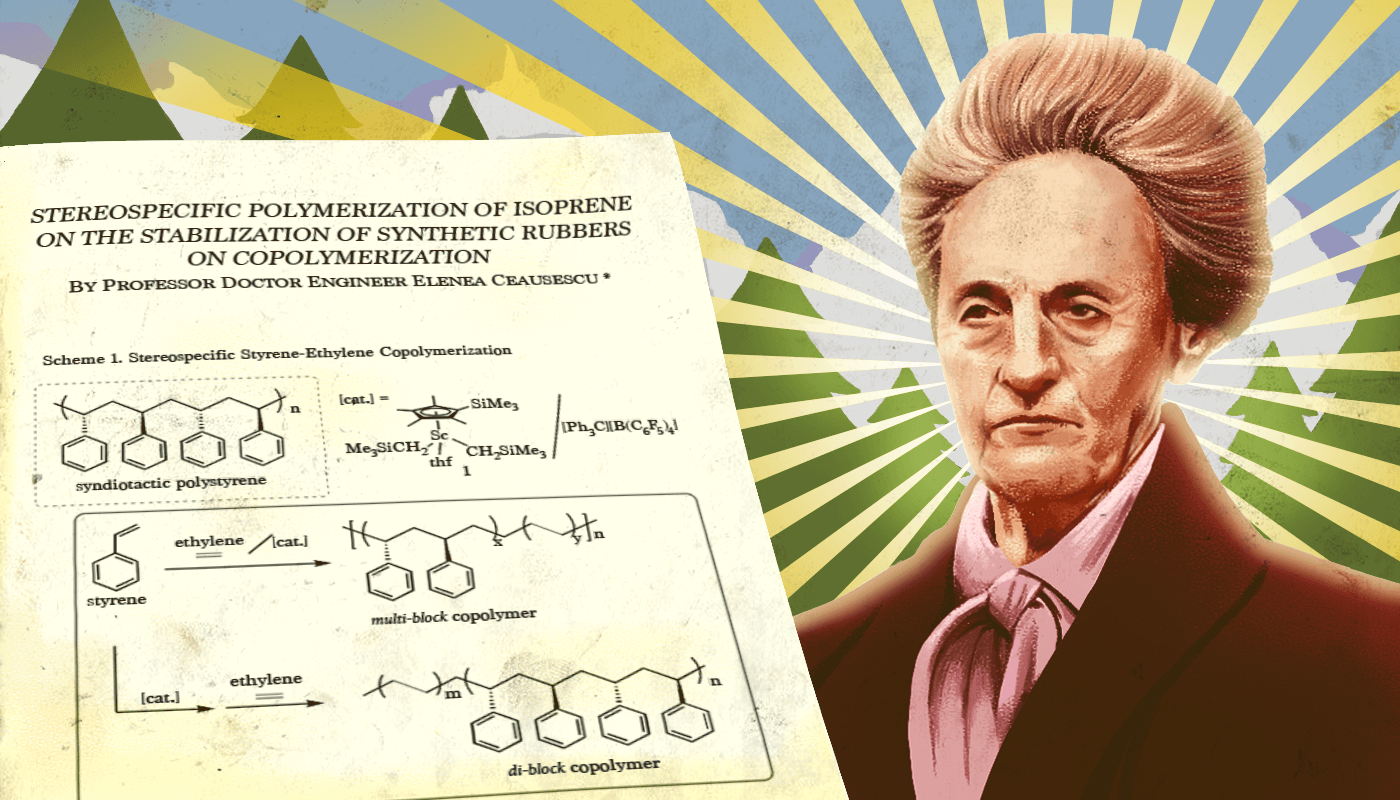

Nevertheless, on December 8, 1967, she obtained a PhD in chemistry after defending her thesis on the "Stereospecific Polymerization of Isoprene on the Stabilization of Synthetic Rubbers on Copolymerization." Romanian law decreed that doctoral candidates had to publicly defend their theses. To avoid the public defense of a thesis that she likely did not write, the law was changed so that she only needed to submit a written defense.

A few days after her "thesis defense," a public presentation of her thesis was scheduled to take place at 7:30 am. Hundreds of people came to listen to the president's wife present her work. What they found when they arrived were closed doors and a note saying that the public presentation had been moved to 6 am and was already over. The presentation never occurred. Indeed, there was nothing to present.

Elena's rise to the top ranks of academic chemists was, subsequently, smooth. Publications steadily appeared under the name of Professor Doctor Engineer Elena Ceaucescu. It was easy for her to find scientists to publish studies and books in her name; they did not have much of a choice and were handsomely rewarded for their work. An entire organization was involved in translating and distributing "her" works. She never wrote a thing herself during her entire life.

Eventually, Elena became the head of Romania's Institute for Chemistry. But that was not enough: Elena wanted every chemical institute in the country to come under one central institute in Bucharest, with herself at the helm.

She wanted to be called Professor Doctor Engineer, and she found no opposition at the Romanian Academy, since resistance was both futile and dangerous.

As Behr explains in his history of the Ceaucescus' reign of terror, Mircea Corcioveci, one of the top scientists at the Institute, eventually discovered that Elena "didn't know what a chromatograph was and didn't recognize the formula for sulfuric acid," which was "taught to first-year chemistry students" (141). Ultimately, she became Chair of the National Council for Science and Technology and controlled all scientific research in the country, although she knew nothing about it.

She wanted to be called Professor Doctor Engineer, and she found no opposition at the Romanian Academy, since resistance was both futile and dangerous. Those few people who dared to resist her demands were removed from their positions.

Forced international "recognition"

Dominance in the scientific establishment within Romania was only one step on Elena's path to prestige. She routinely sought international recognition from other scientists. When the Ceausescus traveled abroad for state visits, ceremonies had to be negotiated prior to the trip in which Elena would receive honorary degrees and other rewards for her scientific work.

Not a single scientist in either the West or the East ever wondered why she never participated in scientific debates.

The couple refused to accept an invitation from a foreign country if an award was not arranged for Elena. These awards included honorary fellowships at foreign universities, even in the West. Not a single scientist in either the West or the East ever wondered why she never participated in scientific debates.

Naturally, Elena sought what was probably the most prestigious scientific honor in Europe: membership in Britain's Royal Society. The ability to add FRS after her name certainly appealed to her, considering her already lengthy list of titles. Prior to attending an official visit to the UK, the Ceausescus solicited the Royal Society, as well as Oxford and Cambridge, for honors.

The petitions were turned down and Elena had to settle for an honorary degree from the Central London Polytechnic and an honorary fellowship from the Royal Institute of Chemistry. According to Behr, the chancellor of London University, Professor Sir Philip Norman, publicly praised Elena's work, despite the fact that she never wrote a single word of any of her publications.

Years later, Corcioveci acknowledged the truth behind Elena's international reputation:

"We were told: no paper can be written or published, no conference delivered without Elena Ceausecu's name appearing in first place. We never saw her, we never heard from her at any time during our research or afterward. She never even acknowledged our existence. We were producing papers with words which, we knew, she could not pronounce, let alone understand." (qtd. in Behr 184)

Her unfortunate mispronunciation of the chemical CO2 as "CO-doi," earned her the unflattering nickname, Codoi, or "long tail" in Romanian.

Indeed, Elena's insistence on her own primacy, as well as her unfortunate mispronunciation of the chemical CO2 as "CO-doi," earned her the unflattering nickname, Codoi ("doi" is the Romanian word for "two") (Kenyon cccxi). It was perhaps not accidental that "Codoi" also means "big tail" in Romanian.

In 1975, she was awarded Doctor Honoris Causa at both the University of Tehran and Jordan University in Amman. Later, the University of Manila awarded Elena with an honorary doctorate thanks to a large donation that the Ceausescus made during a trip to the Philippines.

Elena never admitted to any research malpractice and insisted that institutions really wanted to grant her recognition for her scholarly work.

When the Ceausescus set out for a state visit to the United States in 1978, Elena was offered an honorary membership at the Illinois Academy of Sciences (IAS). However, nothing less than recognition from a Washington-based institute would satisfy her. According to Ion Mihai Pacepa, a former chief of Romania's foreign intelligence service and author of the book Red Horizons: The True Story of Nicolae and Elena Ceausescus' Crimes, Lifestyle, and Corruption, Elena was livid:

"Come off it! You can't sell me the idea that Mr. Peanut [then US President Jimmy Carter] can give me an Illi-whatsis diploma but not any from Washington. I will not go to Illi-whatever it is [sic]. I will not!" (Pacepa 180)

Ultimately, when an offer from a Washington-based organization did not appear, she was forced to accept the honorary membership from the IAS. She showed her disgust and vehement anti-semitism by claiming that she had to accept a "low-ranked" degree from the hands of a "dirty Jew," Dr. Emanuel Merdinger, then head of the IAS (Pacepa 181).

Elena never admitted to any of this and insisted until the end of her life that the institutions really wanted to grant her recognition for her scholarly work.

The end of Elena

In only a matter of days, Elena transformed from one of the most prestigious scientists in Europe to a state criminal facing a firing squad.

All of the scientific honors in the world could not protect Elena from the fall of her husband's regime during the 1989 Romanian Revolution. The Ceausescus were overthrown and both Elena and her husband were captured, tried, and sentenced to death. In only a matter of days, Elena transformed from one of the most prestigious scientists in Europe to a state criminal facing a firing squad.

It was only at this point that she was finally confronted by her fraud. Yet, she did not show any remorse—quite the opposite. She, as well as her husband, insisted, until the very end, that her academic achievements were not only valid, but also well-earned.

A prosecutor asked her: "And who wrote the papers for you, Elena?"

The "trial" that sealed the Ceausecus' fate was perhaps the perfect foil for the decades of falsification and fraud that defined Elena's scientific career. Behr calls the proceedings "farcical" and it is clear that the prosecutors were performing an act of restitution that the entire nation desperately needed.

One question in particular, posed by a prosecutor to Elena, not only sums up the Professor Doctor Engineer's entire trajectory, but also speaks to us today, as more and more instances of research malpractice come to light: "And who wrote the papers for you, Elena?" (qtd. in Behr 24).

Behr, Edward. Kiss the Hand You Cannot Bite: The Rise and Fall of the Ceausescus. Edited by P. Gethers, Villard Books, 1991.

Clogg, Richard. “Let Us Now Praise a Famous Woman: The Questionable Wisdom of British Institutions in Honouring Elena Ceausescu in the Late 1970s.” New Scientist, Jan. 1990, https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg12517004-500-forum-let-us-now-praise-a-famous-woman-the-questionable-wisdom-of-british-institutions-in-honouring-elena-ceausescu-in-the-late-1970s/.

“Die Traumkarriere Der Elena Ceausescu.” Mdr.De, 5 Mar. 2018, https://www.mdr.de/geschichte/elena-ceausescu-100.html.

Elena Ceausescu: Doctor Horroris. Youtube, 21 Aug. 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LSoxcc6ZPoI.

Hanson, Roger. “Elena Ceausescu - Romanian Dictator’s Wife and Fake Scientist.” Stuff.Co.Nz, 12 July 2017, https://www.stuff.co.nz/science/94679348/roger-hanson-elena-ceausescu--romanian-dictators-wife-and-fake-scientist.

Kenyon, Paul. Children of the Night: The Strange and Epic Story of Modern Romania. Apollo, 2021.

Pacepa, Ion Mihai, and Mihai Pacepa. Red Horizons: The True Story of Nicolae and Elena Ceasescus’ Crimes, Lifestyle, and Corruption. Regnery Publishing, 1987.