Have you ever wondered what religion and computing have in common? The answer is Father Roberto Busa. His work combined both fields and what came out of it shaped the future of computing in the humanities.

The merging of the priest’s vision and IBM’s machine created what we call now hypertext.

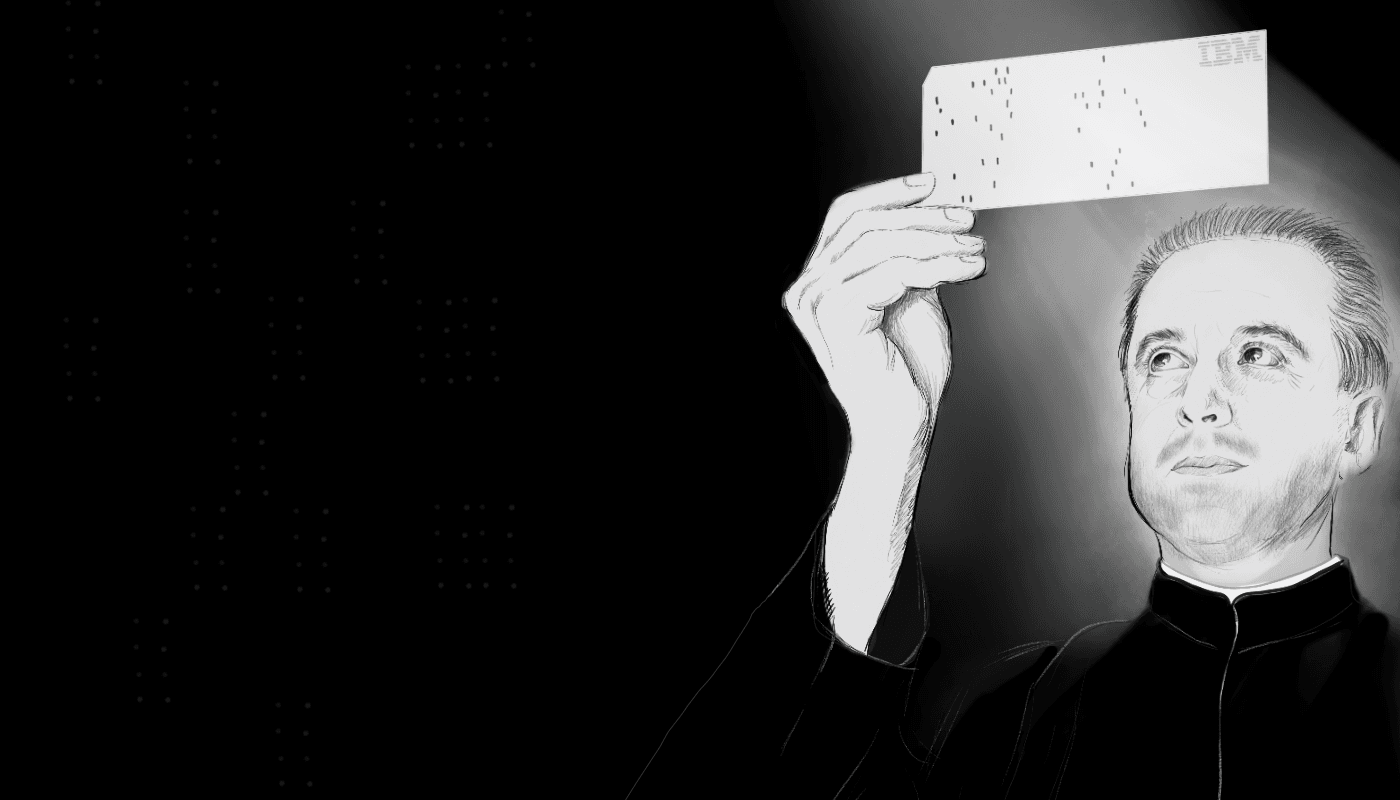

If you are able to read this website, you owe it to Father Busa. In 1928, IBM innovated the world with a new version of the punch card machine. Busa helped improve this machine. The merging of the priest’s vision and IBM’s machine created what we call now hypertext. This meant that the punch card machine did not only crunch numbers but gather, categorize and connect words too. The priest's innovative vision in humanities allowed everyone to easily search and analyze written works.

10,000 handwritten index cards — not enough

Father Busa's unique project attracted the attention of many academics.

An Italian Jesuit priest pursuing a PhD at the Pontifical Gregorian University of Rome had submitted his final thesis. His project started out with the question: “What is the metaphysics of presence in St. Thomas Aquinas?” St. Thomas doctrine of presence (the belief that Jesus is substantially present in the Eucharist, not merely symbolically) was connected to the preposition “in”. Giving his own perspective on the meaning of “presence”, Roberto Busa began the study of how function-words influence meaning-words. In order to carry out the study, he needed the different meanings of the word “in”. Therefore, his dissertation (1946) was based on a Thomistic Concordance -a type of systematic index of words used in a written work- made by himself. He had written 10,000 cards by hand. That’s called dedication.

At the International Congress of Philosophy in Barcelona in 1948, the young priest argued to first understand the definition of words in the mind of an author before trying to figure out the collective meaning of the work. As a result, he planned an extended version of his Thomistic Concordance, including conjunctions, prepositions, and pronouns, just like dismantled phrases. All these, to understand every word's core meaning. This record would require around 13 million cards.

He divided the project in two parts:

- a record including all words of St. Thomas Aquinas. Every card in the file would include a particular word in the upper left corner. Underneath, the reference to the place where the word appears in the text, along with a part of the sentence in which the word is found.

- an Index and Concordance would derive from such record.

This would not be an easy task. At that time such a system attracted the attention of many academics. Busa called out for information about any mechanical device that could accomplish such task.

Convincing IBM to try the impossible

There was only one company capable of creating what Busa envisioned, and it was called IBM.

He started the hunt for mechanical aid. In the USA, automated control of cards was already a dominant business. Therefore, Father Busa set out to the United States in search of a business partner. His search took him to around twenty-five universities, which led him ultimately to meet the one and only, Thomas J. Watson, the founder of IBM.

There was only one company capable of creating what Busa envisioned, and it was called IBM. IBM’s industry was based on Hermann Hollerith’s patents, a system of recording information by punching holes in sheets of paper. Hollerith preceded the creation of the electronic calculating punch card machine, with which IBM innovated the world.

On his way into Watson's office, Busa grabbed a small poster from the wall that read, “The difficult we do right away; the impossible takes a little longer.”

As Thomas Nelson Winter wrote in his piece “Roberto Busa S.J. and the Invention of the Machine-Generated Concordance,” Busa learned Watson's engineers had already advised him not to collaborate with the task, as it would be impossible. So, on his way into Watson's office, Busa grabbed a small poster from the wall that read, “The difficult we do right away; the impossible takes a little longer.” The priest showed the executive his own company's slogan, and Watson agreed with IBM's cooperation.

And it took longer indeed. Father Busa’s project was published -in print form- in the 1970’s, but it wasn’t until 20 years later that the work was finally available on CD-ROM. Since 2005 his work, Index Thomisticus, can also be accessed online. The priest invested nearly 50 years of his life in the project. If you ever complained about not having finished your thesis yet, this is motivation.

How to make a machine understand words

The indexing technique developed by Busa and IBM introduced a new era of “language engineering” and paved the way for modern hypertext.

At this point, you might have an idea of how words were introduced to a machine that could only handle numbers. But it's time to dive into a more technical explanation.

In 1948 the IBM 604 Electronic Calculating Punch hit the market. This sophisticated version could perform addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division with electronic speed, and execute up to twenty program steps between reading data from a card and punch out the result.

As Father Busa explained in his book Varia Specimina, his version of the machine used 5 program steps:

- First, they took each line of a written work to be punched onto a card — as position coded holes — at the first station, the automatic punch. This part was regulated by a keyboard and was thus the only human input. From this point on, cards would be error-free, as the machine was able to proofread each card. This station was called Collator. Each line was typed in twice, if the collator saw no difference, both were correct; if there was a difference, a typo would be flagged, and the line was re-punched. The rest was largely a matter of supervising the machines.

- At the next station, the Record Interpreter printed what was 'written' in the holes.

- The following station, the Reproducer made a copy of each card, and next to it the first word of the line. Then a second copy with the second word of the line. Finally, there were as many cards as words in the text.

- At this point, alphabetizing was a matter of feeding the Sorter Machine. This had to be done manually.

- The last stop was the Alphanumeric Accounting Machine, or Tabulator. This re-transcribed the words in the holes in the cards into letters and numbers. A print-out, basically.

As Father Busa expressed in his preface: “The concordance which I am presenting as an example is precisely an off-set reproduction of tabulated sheets turned out by the accounting machine.” The new machine, released in 1951, proved that accounting machines could produce a concordance. The coding and indexing techniques developed by Busa and IBM introduced a fast method of literature searching, and started a new era of “language engineering.”

Takeaways for academics in 2019

Father Roberto Busa was a true scholar and his life's work serves as an outstanding example of how to approach a research project and a career:

- Find your field and specific topic of interest

- Develop a project for a couple of years

- Tell everyone about it

- Get good connections

- Persuade some connections to invest in your project

- Work on it for 50 more years 😅