How to make a scientific presentation

A good scientific presentation achieves three things: you communicate the science clearly, your research leaves a lasting impression on your audience, and you enhance your reputation as a scientist.

But, what is the best way to prepare for a scientific presentation? How do you start writing a talk? What details do you include, and what do you leave out?

It’s tempting to launch into making lots of slides. But, starting with the slides can mean you neglect the narrative of your presentation, resulting in an overly detailed, boring talk.

The key to making an engaging scientific presentation is to prepare the narrative of your talk before beginning to construct your presentation slides. Planning your talk will ensure that you tell a clear, compelling scientific story that will engage the audience.

In this guide, you’ll find everything you need to know to make a good oral scientific presentation, including:

- The different types of oral scientific presentations and how they are delivered

- How to outline a scientific presentation

- How to make slides for a scientific presentation

Our advice results from delving into the literature on writing scientific talks and from our own experiences as scientists in giving and listening to presentations. We provide tips and best practices for giving scientific talks in a separate post.

Scientific presentation outlines

There are two main types of scientific talks:

- Your talk focuses on a single study. Typically, you tell the story of a single scientific paper. This format is common for short talks at contributed sessions in conferences.

- Your talk describes multiple studies. You tell the story of multiple scientific papers. It is crucial to have a theme that unites the studies, for example, an overarching question or problem statement, with each study representing specific but different variations of the same theme. Typically, PhD defenses, invited seminars, lectures, or talks for a prospective employer (i.e., “job talks”) fall into this category.

➡️ Learn how to prepare an excellent thesis defense

Questions to ask yourself before you write your talk

1. How much time do you have?

The length of time you are allotted for your talk will determine whether you will discuss a single study or multiple studies, and which details to include in your story.

2. Who will you speak to?

The background and interests of your audience will determine the narrative direction of your talk, and what devices you will use to get their attention. Will you be speaking to people specializing in your field, or will the audience also contain people from disciplines other than your own? To reach non-specialists, you will need to discuss the broader implications of your study outside your field.

The needs of the audience will also determine what technical details you will include, and the language you will use. For example, an undergraduate audience will have different needs than an audience of seasoned academics. Students will require a more comprehensive overview of background information and explanations of jargon but will need less technical methodological details.

Your goal is to speak to the majority. But, make your talk accessible to the least knowledgeable person in the room.

3. What do you want the audience to learn from your talk?

This is called the thesis statement, or simply the “take-home message”. Having listened to your talk, what message do you want the audience to take away from your presentation? Describe the main idea in one or two sentences. You want this theme to be present throughout your presentation. Again, the thesis statement will depend on the audience and the type of talk you are giving.

Your thesis statement will drive the narrative for your talk. By deciding the take-home message you want to convince the audience of as a result of listening to your talk, you decide how the story of your talk will flow and how you will navigate its twists and turns. The thesis statement tells you the results you need to show, which subsequently tells you the methods or studies you need to describe, which decides the angle you take in your introduction.

➡️ Learn how to write a thesis statement

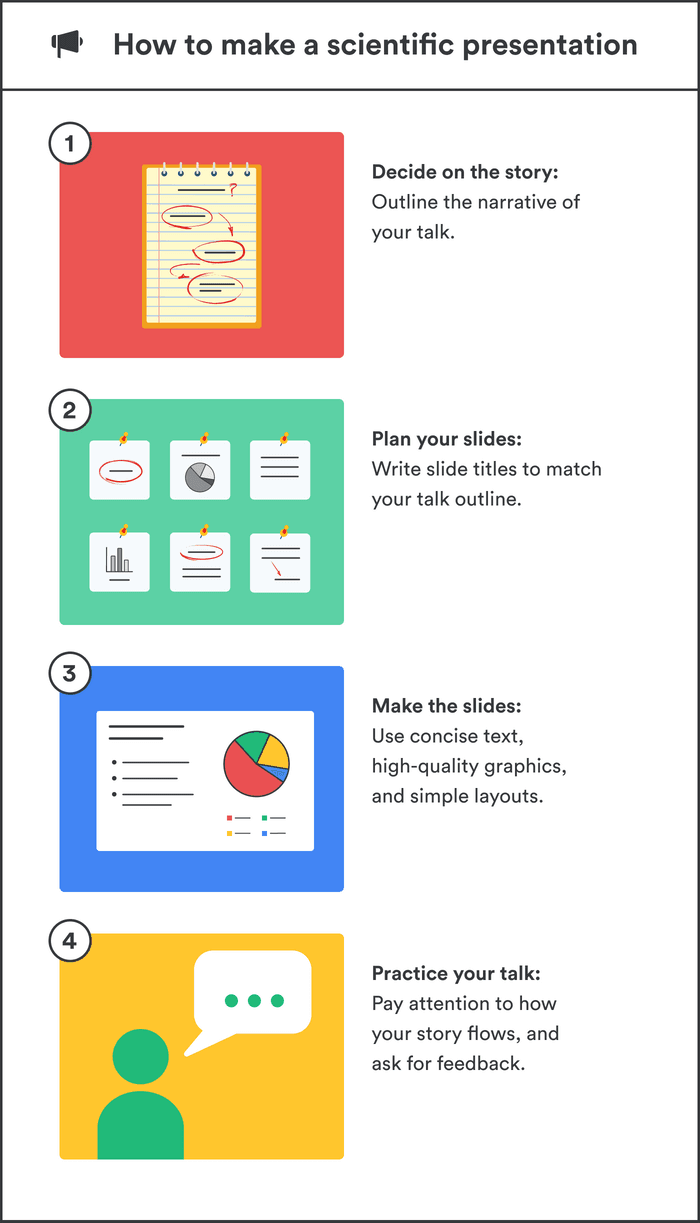

How to make a scientific presentation

The goal of your talk is for the audience to leave afterward with a clear understanding of the key takeaway message of your research. To achieve that goal, you need to tell a coherent, logical story that conveys your thesis statement throughout the presentation. You can tell your story through careful preparation of your talk.

Preparation of a scientific presentation involves three separate stages: outlining the scientific narrative, preparing slides, and practicing your delivery. Making the slides of your talk without first planning what you are going to say is inefficient.

Here, we provide a 4-step guide to writing your scientific presentation:

- Outline your presentation

- Plan your presentation slides

- Make the presentation slides

- Practice your presentation

Step 1: Outline your presentation

Writing an outline helps you consider the key pieces of your talk and how they fit together from the beginning, preventing you from forgetting any important details. It also means you avoid changing the order of your slides multiple times, saving you time.

Plan your talk as discrete sections. In the table below, we describe the sections for a single study talk vs. a talk discussing multiple studies:

| Sections in a single study talk | Sections in a talk with multiple studies |

|---|---|

Introduction | Introduction - main idea behind all studies |

Methods | Methods of study 1 |

Results | Results of study 1 |

Summary (take-home message ) of study 1 | |

Transition to study 2 (can be a visual of your main idea that return to) | |

Brief introduction for study 2 | |

Methods of study 2 | |

Results of study 2 | |

Summary of study 2 | |

Transition to study 3 | |

Repeat format until done | |

Summary | Summary of all studies (return to your main idea) |

Conclusion | Conclusion |

The following tips apply when writing the outline of a single study talk. You can easily adapt this framework if you are writing a talk discussing multiple studies.

Introduction: Writing the introduction can be the hardest part of writing a talk. And when giving it, it’s the point where you might be at your most nervous. But preparing a good, concise introduction will settle your nerves.

The introduction tells the audience the story of why you studied your topic. A good introduction succinctly achieves four things, in the following order.

- It gives a broad perspective on the problem or topic for people in the audience who may be outside your discipline (i.e., it explains the big-picture problem motivating your study).

- It describes why you did the study, and why the audience should care.

- It gives a brief indication of how your study addressed the problem and provides the necessary background information that the audience needs to understand your work.

- It indicates what the audience will learn from the talk, and prepares them for what will come next.

A good introduction not only gives the big picture and motivations behind your study but also concisely sets the stage for what the audience will learn from the talk (e.g., the questions your work answers, and/or the hypotheses that your work tests). The end of the introduction will lead to a natural transition to the methods.

Give a broad perspective on the problem. The easiest way to start with the big picture is to think of a hook for the first slide of your presentation. A hook is an opening that gets the audience’s attention and gets them interested in your story. In science, this might take the form of a why, or a how question, or it could be a statement about a major problem or open question in your field. Other examples of hooks include quotes, short anecdotes, or interesting statistics.

Why should the audience care? Next, decide on the angle you are going to take on your hook that links to the thesis of your talk. In other words, you need to set the context, i.e., explain why the audience should care. For example, you may introduce an observation from nature, a pattern in experimental data, or a theory that you want to test. The audience must understand your motivations for the study.

Supplementary details. Once you have established the hook and angle, you need to include supplementary details to support them. For example, you might state your hypothesis. Then go into previous work and the current state of knowledge. Include citations of these studies. If you need to introduce some technical methodological details, theory, or jargon, do it here.

Conclude your introduction. The motivation for the work and background information should set the stage for the conclusion of the introduction, where you describe the goals of your study, and any hypotheses or predictions. Let the audience know what they are going to learn.

Methods: The audience will use your description of the methods to assess the approach you took in your study and to decide whether your findings are credible. Tell the story of your methods in chronological order. Use visuals to describe your methods as much as possible. If you have equations, make sure to take the time to explain them. Decide what methods to include and how you will show them. You need enough detail so that your audience will understand what you did and therefore can evaluate your approach, but avoid including superfluous details that do not support your main idea. You want to avoid the common mistake of including too much data, as the audience can read the paper(s) later.

Results: This is the evidence you present for your thesis. The audience will use the results to evaluate the support for your main idea. Choose the most important and interesting results—those that support your thesis. You don’t need to present all the results from your study (indeed, you most likely won’t have time to present them all). Break down complex results into digestible pieces, e.g., comparisons over multiple slides (more tips in the next section).

Summary: Summarize your main findings. Displaying your main findings through visuals can be effective. Emphasize the new contributions to scientific knowledge that your work makes.

Conclusion: Complete the circle by relating your conclusions to the big picture topic in your introduction—and your hook, if possible. It’s important to describe any alternative explanations for your findings. You might also speculate on future directions arising from your research. The slides that comprise your conclusion do not need to state “conclusion”. Rather, the concluding slide title should be a declarative sentence linking back to the big picture problem and your main idea.

It’s important to end well by planning a strong closure to your talk, after which you will thank the audience. Your closing statement should relate to your thesis, perhaps by stating it differently or memorably. Avoid ending awkwardly by memorizing your closing sentence.

Step 2: Plan your presentation slides

By now, you have an outline of the story of your talk, which you can use to plan your slides. Your slides should complement and enhance what you will say. Use the following steps to prepare your slides.

- Write the slide titles to match your talk outline. These should be clear and informative declarative sentences that succinctly give the main idea of the slide (e.g., don’t use “Methods” as a slide title). Have one major idea per slide. In a YouTube talk on designing effective slides, researcher Michael Alley shows examples of instructive slide titles.

- Decide how you will convey the main idea of the slide (e.g., what figures, photographs, equations, statistics, references, or other elements you will need). The body of the slide should support the slide’s main idea.

- Under each slide title, outline what you want to say, in bullet points.

In sum, for each slide, prepare a title that summarizes its major idea, a list of visual elements, and a summary of the points you will make. Ensure each slide connects to your thesis. If it doesn’t, then you don’t need the slide.

Step 3: Make the presentation slides

Slides for scientific presentations have three major components: text (including labels and legends), graphics, and equations. Here, we give tips on how to present each of these components.

Slide design

- Have an informative title slide. Include the names of all coauthors and their affiliations. Include an attractive image relating to your study.

- Make the foreground content of your slides “pop” by using an appropriate background. Slides that have white backgrounds with black text work well for small rooms, whereas slides with black backgrounds and white text are suitable for large rooms.

- The layout of your slides should be simple. Pay attention to how and where you lay the visual and text elements on each slide. It’s tempting to cram information, but you need lots of empty space. Retain space at the sides and bottom of your slides.

Text elements

- Use sans serif fonts with a font size of at least 20 for text, and up to 40 for slide titles. Citations can be in 14 font and should be included at the bottom of the slide.

- Use bold or italics to emphasize words, not underlines or caps. Keep these effects to a minimum.

- Use concise text. You don’t need full sentences. Convey the essence of your message in as few words as possible. Write down what you’d like to say, and then shorten it for the slide. Remove unnecessary filler words.

- Text blocks should be limited to two lines. This will prevent you from crowding too much information on the slide.

- Include names of technical terms in your talk slides, especially if they are not familiar to everyone in the audience.

- Proofread your slides. Typos and grammatical errors are distracting for your audience.

- Include citations for the hypotheses or observations of other scientists.

Graphics

- Good figures and graphics are essential to sustain audience interest. Use graphics and photographs to show the experiment or study system in action and to explain abstract concepts.

- Don’t use figures straight from your paper as they may be too detailed for your talk, and details like axes may be too small. Make new versions if necessary. Make them large enough to be visible from the back of the room.

- Use graphs to show your results, not tables. Tables are difficult for your audience to digest! If you must present a table, keep it simple.

- Label the axes of graphs and indicate the units. Label important components of graphics and photographs and include captions. Include sources for graphics that are not your own.

- Explain all the elements of a graph. This includes the axes, what the colors and markers mean, and patterns in the data.

- Use colors in figures and text in a meaningful, not random, way. For example, contrasting colors can be effective for pointing out comparisons and/or differences. Don’t use neon colors or pastels.

- Use thick lines in figures, and use color to create contrasts in the figures you present. Don’t use red/green or red/blue combinations, as color-blind audience members can’t distinguish between them.

- Arrows or circles can be effective for drawing attention to key details in graphs and equations. Add some text annotations along with them.

- Write your summary and conclusion slides using graphics, rather than showing a slide with a list of bullet points. Showing some of your results again can be helpful to remind the audience of your message.

Equations

- If your talk has equations, take time to explain them. Include text boxes to explain variables and mathematical terms, and put them under each term in the equation.

- Combine equations with a graphic that shows the scientific principle, or include a diagram of the mathematical model.

Animations and transitions

- Use animations judiciously. They are helpful to reveal complex ideas gradually, for example, if you need to make a comparison or contrast or to build a complicated argument or figure. For lists, reveal one bullet point at a time. New ideas appearing sequentially will help your audience follow your logic.

- Slide transitions should be simple. Silly ones distract from your message.

- Decide how you will make the transition as you move from one section of your talk to the next. For example, if you spend time talking through details, provide a summary afterward, especially in a long talk. Another common tactic is to have a “home slide” that you return to multiple times during the talk that reinforces your main idea or message. In her YouTube talk on designing effective scientific presentations, Stanford biologist Susan McConnell suggests using the approach of home slides to build a cohesive narrative.

Step 4: Practice your presentation

To deliver a polished presentation, it is essential to practice it. Here are some tips.

- For your first run-through, practice alone. Pay attention to your narrative. Does your story flow naturally? Do you know how you will start and end? Are there any awkward transitions? Do animations help you tell your story? Do your slides help to convey what you are saying or are they missing components?

- Next, practice in front of your advisor, and/or your peers (e.g., your lab group). Ask someone to time your talk. Take note of their feedback and the questions that they ask you (you might be asked similar questions during your real talk).

- Edit your talk, taking into account the feedback you’ve received. Eliminate superfluous slides that don’t contribute to your takeaway message.

- Practice as many times as needed to memorize the order of your slides and the key transition points of your talk. However, don’t try to learn your talk word for word. Instead, memorize opening and closing statements, and sentences at key junctures in the presentation. Your presentation should resemble a serious but spontaneous conversation with the audience.

- Practicing multiple times also helps you hone the delivery of your talk. While rehearsing, pay attention to your vocal intonation and speed. Make sure to take pauses while you speak, and make eye contact with your imaginary audience.

- Make sure your talk finishes within the allotted time, and remember to leave time for questions. Conferences are particularly strict on runtime.

- Anticipate questions and challenges from the audience, and clarify ambiguities within your slides and/or speech in response.

- If you anticipate that you could be asked questions about details but you don’t have time to include them, or they detract from the main message of your talk, you can prepare slides that address these questions and place them after the final slide of your talk.

Final thoughts

An organized presentation with a clear narrative will help you communicate your ideas effectively, which is essential for engaging your audience and conveying the importance of your work. Taking time to plan and outline your scientific presentation before writing the slides will help you manage your nerves and feel more confident during the presentation, which will improve your overall performance.

Frequently Asked Questions about Preparing scientific presentations

🎭 What makes a good scientific presentation?

A good scientific presentation has an engaging scientific narrative with a memorable take-home message. It has clear, informative slides that enhance what the speaker says. You need to practice your talk many times to ensure you deliver a polished presentation.

🐿️ How do you prepare for a scientific presentation?

First, consider who will attend your presentation, and what you want the audience to learn about your research. Tailor your content to their level of knowledge and interests. Second, create an outline for your presentation, including the key points you want to make and the evidence you will use to support those points. Finally, practice your presentation several times to ensure that it flows smoothly and that you are comfortable with the material.

❓ How do you start a scientific presentation?

Prepare an opening that immediately gets the audience’s attention. A common device is a why or a how question, or a statement of a major open problem in your field, but you could also start with a quote, interesting statistic, or case study from your field.

🚴♀️ How do you structure a scientific presentation?

Scientific presentations typically either focus on a single study (e.g., a 15-minute conference presentation) or tell the story of multiple studies (e.g., a PhD defense or 50-minute conference keynote talk). For a single study talk, the structure follows the scientific paper format: Introduction, Methods, Results, Summary, and Conclusion, whereas the format of a talk discussing multiple studies is more complex, but a theme unifies the studies.

💻 How do you make a good scientific presentation slide?

Ensure you have one major idea per slide, and convey that idea clearly (through images, equations, statistics, citations, video, etc.). The slide should include a title that summarizes the major point of the slide, should not contain too much text or too many graphics, and color should be used meaningfully.